Margaret Marsh and Wanda Ronner:

Assisted Reproductive Technology and the Pursuit of Parenthood

Welcome to this website, which focuses on our research in the history of reproductive technology and medicine. We are Margaret Marsh, a historian, and Wanda Ronner, a gynecologist. Our most recent book, The Pursuit of Parenthood: Reproductive Technology from Test-Tube Babies to Uterus Transplants, explores the history of assisted reproduction and the lessons of that history for the present day. Our research was funded by an Investigator Award in Health Policy Research from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Published in 2019 by Johns Hopkins University Press, The Pursuit of Parenthood was a 2020 finalist for the PROSE Award for Best Book in History of Science, Medicine and Technology.

The Pursuit of Parenthood complements our previous two books on the history of infertility, reproductive sexuality, and reproductive medicine, subjects we’ve been studying for close to three decades now. Our first book, The Empty Cradle: Infertility in America from Colonial Times to the Present, provided a comprehensive history of the attitudes towards, the experience of, and the medical treatment for, infertility beginning in the colonial period. Our second, The Fertility Doctor: John Rock and the Reproductive Revolution, explored the development of the field of reproductive medicine through the life and career of one of the most prominent infertility specialists of the mid-twentieth century, John Rock, who later became famous as the co-developer of the oral contraceptive.

After we spent so many years thinking and writing about fertility and infertility in history, we wanted to bring our unique perspective to the late twentieth and early twenty-first century transformation in reproductive medicine and technology. The Pursuit of Parenthood, like our earlier books, reflects our intense interest in the linkages among medical research and practice, the experiences of patients, and the cultural and political frameworks within which the interactions between people and their doctors take place. In this one, we explore the interconnected stories of the scientists and physicians who developed and employed the new reproductive technologies (often united under the singular term assisted reproductive technology) and of the women and men who use – or in some cases are unable to use – them. The book also examines the overlapping social, political, and cultural frameworks in which these technologies were developed, and it explores the moral and ethical controversies they engender.

Some people have asked us: What exactly is “assisted reproductive technology”?

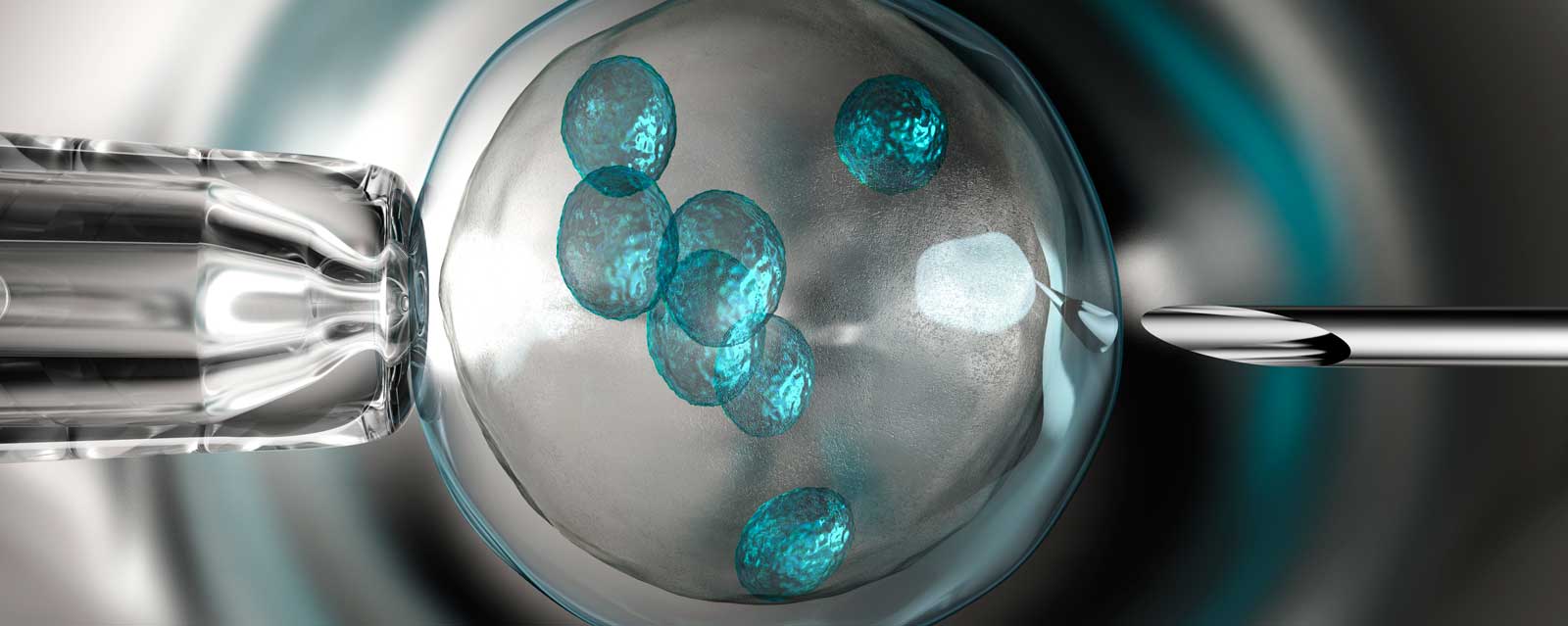

“Assisted Reproductive Technology,” abbreviated ART and sometimes called “assisted reproduction,” is the term used to describe in vitro fertilization (IVF) and related procedures. ART refers to procedures in which eggs and/or embryos are handled outside the body. Not every procedure to treat infertility is an assisted reproductive technology. For example, artificial insemination, unless it is combined with in vitro fertilization, is a medical treatment but not an assisted reproductive technology, because it does not involve handling eggs or embryos outside the body.

In vitro fertilization has a longer history than you might think. Attempts at IVF in animals date all the way back to the 19th century. And the first published report of fertilization of a human egg outside the body came in 1944, when John Rock and Miriam Menkin announced in Science Magazine that they had fertilized four human eggs “in glass,” the English translation of the term “in vitro.”

But it wasn’t until the 1970s that researchers were able actually to achieve pregnancy and birth from an egg fertilized in vitro. From the late 1960s onward, researchers, first in England and then in Australia, were fertilizing eggs, then beginning to implant them, and, sometimes achieving a pregnancy. In 1978 the British team of Patrick Steptoe and Robert Edwards, assisted by technician Jean Purdy, were the first to succeed. Louise Brown was born in Oldham England, just outside Manchester, on July 25, 1978.

England? Australia? Why not the U.S.?

That’s a good question. Some American researchers had done research in animals and wanted to proceed to human applications. But the American political climate was, to say the least, unfavorable. In 1975 the federal government, the source of most scientific funding in the U.S. since the 1950s, declared a temporary “moratorium” on the funding of human embryo research.

The ban – which under a different name is still in effect, by the way — did halt IVF attempts, at least temporarily. But Louise Brown’s birth altered the American research landscape. After all, the federal government refused to fund IVF research, but there were no laws against doctors attempting to do it on their own. In 1980 the first IVF clinic in the U.S. opened, and others soon followed. Without federal government funding or regulation, the private sector took over. In other parts of the world, the United States became known as the “wild west of reproductive medicine.”

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, we still have a nation riven by conflict over a host of reproductive issues, including access to birth control and abortion. But contraception and abortion are not the only reproductive questions we face. Americans also have profound disagreements over multiple aspects of assisted reproductive technology.

Is the U.S. still the “wild west” when it comes to reproductive medicine?

The very idea of creating an embryo outside of a woman’s body was controversial in the 1970s. Today, though, heterosexual married couples with wives in their 20s, 30s, or early 40s who have the procedure using their own eggs and sperm barely raise an eyebrow. But there are still divisions over other issues. Some examples: Should doctors be providing IVF to women in their fifties and sixties? (These women also need donor eggs. They are too old to produce their own.) Should we encourage women to freeze their eggs in their thirties in the hope they might be able to use them in their forties? Is the use of pre-implantation genetic screening (PGS), or pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) a step on the way to creating designer babies? A possible devaluation of existing children who have been born with a disability? Or — are they mechanisms to prevent suffering in a potential child?

As a nation, we have been unable to reach a consensus on whether these technologies should be regulated, and if so, which ones? In which ways? As a result, the U. S. – by default rather than design – has let the market determine what kinds of technologies are developed, how they are used, and who can access them. Over the years, legislators and judges, bio-ethics experts and physicians, the women and men who seek fertility treatment, and the public, have argued over such matters as the ethics of egg and embryo donation (or sale), gestational surrogacy, the use of assisted reproduction by same-sex couples and unmarried men and women, racial and socioeconomic disparities in access to care, IVF for women past the age of menopause, elective egg freezing by women seeking to preserve their fertility in the event they fail to have children during their prime reproductive years, the creation of “three-parent” embryos, pre-implantation genetic diagnosis and screening, and mandated health insurance coverage for assisted reproduction.

Some of these questions have been resolved, while other long-standing controversies smolder and new disagreements arise. And we still lack national policies on most of these issues. It is true that a number of states have laws or judicial rulings, for example those bearing on issues such as whose wishes should prevail in cases where one partner wants to use a frozen embryo and the other wants it destroyed, or whether gestational surrogacy contracts should be honored or declared unenforceable. In our judgment, leaving these decisions to the states creates a confused and conflicting legal tangle for potential parents to navigate and is no substitute for thoughtful national policies.

So in short, yes, we are still the wild west of reproductive medicine. One of the goals of our work has been to recommend ways in which such a situation might be addressed.